Instagram: A new identity for the descendants of indentureship

By Aratrika Ganguly

Picture: ‘Coolies’ in the depot in Paramaribo before 1885. Picture by Julius Eduard Muller on Wikimedia Commons.

Indentured servitude started in the Indian subcontinent in 1834 after the abolition of slavery. Thousands of people, mainly from the central and eastern provinces of India, were sent to colonial plantations within the country and to places like British Guyana, South Africa, Fiji, Malaysia etc. These labourers were called by the derogatory term of ‘coolie’. Indentured servitude exploited people in every sense. The descendants of the Indian indenture system, i.e. the descendants of the ‘coolies’ from India, are now settled in various parts of the world.

The word coolie originally had different origins. In the British period, labourers were often termed ‘coolies’. It was a negative racial term hinting at the people who used to do menial or low-wage jobs. Several dictionaries define ‘coolie’ as an unskilled labourer employed cheaply, especially one brought from Asia. Several also flag it as pejorative.

Recently the descendants of this indentured labour system have begun to create a space for themselves by depicting their culture and that of their ancestors via social media.

Fig.1. The definition of indentured servitude

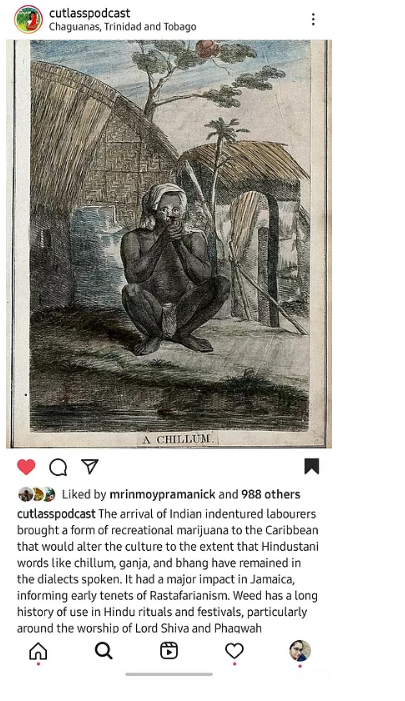

Fig.2. Depiction of a ‘coolie’ smoking ganja

Social media has been an integral part of our lives in contemporary times. It is not just a medium of entertainment, but an essential part of life. People can share content, pictures, and glimpses of their lives with others without the limitations of physical boundaries.

Instagram is an important platform for this collective social psyche where one has a sort of ‘digital life’ and shares it with others.

The descendants of indentureship are very active as content creators and as audiences. Accounts like @jahajee_sisters (Fig.3.) and @thebgdiaries regularly hold events and post about social issues regarding the indenture diaspora. Conversely, accounts like @coolie_tings (Fig. 4), and @coolieconnections post memes that help counteract their violent history with a tinge of humour.

Hashtags are another way by which we can easily and quickly find content on a topic we are interested in. At first, this style of grouping content under a category was used on Twitter. It then made its way to other social media networking sites, including Instagram. Some examples of popular hashtags for content on indentured history and present scenarios are: #coolie, #indenturelabour, #girmitiya, and #indenturedservitude. Not all posts are about South Asian ‘coolies’, however, as many other communities were also forced to work as ‘coolies’. There are some users such as @breakingbrownsilence (Fig.5) and @tessaalexanderart that aim to decolonise history and give voice to their ancestors via their personal accounts. When the ‘coolies’ went to many countries from India, they took their cultural elements with them. Thus, some remained and assimilated with their new society. The Instagram account @cutlasspodcast informs us in one of their posts from 21 April 2021 (Fig.2) that a type of recreational marijuana, the Indian term being ganja, might have come to the Caribbean islands with the Indian ‘coolies’ among other things.

Fig.3. The account of @jahajee_sisters

Fig.4. Meme becomes a medium to express oneself

Fig.5. Instagram becomes a way for decolonising one’s mind and giving voice to the descendants of the indentured labour, the ‘coolies’

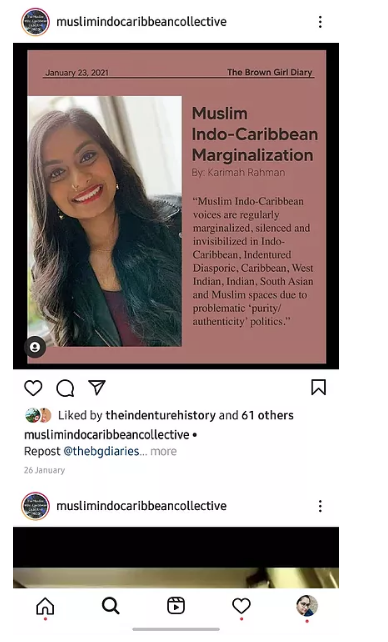

In his book, Diaspora Theory and Transnationalism, Prof. Himadri Lahiri has described diaspora: ‘The concept of homeland alters with later generations of diasporic people. Diaspora is a phenomenon involving uprooting, forced or voluntary, of a mass of people from the “homeland” and their “re-rooting” in the hostland(s).’ The remembrance of the homeland lingers; however, cultural assimilation of the host country simultaneously takes place, and their identity takes on a new shape. Diasporas are rooted in a specific spatio-temporal reality. The same can be said about the ‘coolie’ diaspora. Instagram accounts like @theindenturehistory, @cutlasspodcast, @thebidesiaproject, @coolie.women, @jahajee_sisters (Fig.3) help in finding the spatio-temporal reality, a viewpoint from the descendants of indenture. In the contemporary period, the distance of the diaspora ceases with the visual culture of Instagram. Therefore, when viewers see posts of @muslimindocaribbeancollective (Fig.6.) about the marginalisation of Muslim women of Indo-Caribbean descent, it can be more engaging than reading about the same issue through traditional media channels. Viewers can finally get to understand the multilingual and pluricultural identity of these people. Many find their own ancestry by looking at these accounts or have stories running in their families that speak of indenture.

These accounts help them to create art, remember their history, forge their shared identity with other descendants of indentureship, and support transnational engagements with people all over the world. It has become sort of an archive of history, of ‘coolitude’, and a medium connecting both past and present generations of the diaspora.

The whole purpose of a digital world is to stay connected with each other. Instagram as a visual platform provides this medium to know a part of the ‘other’, framed within the four walls of a digital device. As Instagram is part of a very visual culture, it resonates more with its viewers and audiences. Even if somebody does not have a relationship with the indenture diaspora, they can still feel some connection as oppression still survives in some form or the other, as with the cyber ‘coolies’ who emigrate from India to various parts of the world. Even some Indian labourers migrate as bonded labourers (within India) to work as construction workers or house helpers or, if they are unfortunate, they may become a part of the flesh trade. Many women and men are regularly coaxed to migrate from the remote parts of India in the name of earning a big fortune and, in return, all they get is oppression. The Instagram accounts handled by the descendants of the ‘coolies’ show us a glimpse of the past by providing contents such as old pictures of documents, family photographs, artworks, pictures of ‘coolie’ depot and other historical buildings and places; and capture the life of the contemporary descendants by showing pictures, reels, slogans, quotes, memes, and artworks of various places across the world. The virtual media of Instagram dissolves the border between the homeland of their ancestors and their present homeland by showing them together in a single virtual space. Hence, the border is becoming more porous by the day.

Fig.6. The marginalisation of Indo Caribbean Muslim women

Aratrika Ganguly

Aratrika Ganguly is pursuing a PhD in the Department of Comparative Indian Language and Literature, University of Calcutta. She is currently delivering lectures as a guest lecturer in three colleges under the University of Calcutta. She is the Co-Founder and Coordinator of Calcutta Comparatists 1919, an independent forum for research scholars of Humanities and Social Sciences. Her research area for her PhD is Coolie and Migration and their literature. Her interest lies in the areas of South Asia, Southeast Asia, Coolie Literature, Migration, Women Narrative, Performance Studies, and African Literature. She completed her MPhil in Comparative Literature from Jadavpur University, Kolkata. She also worked as a UGC-UPE-II Project Fellow at the Department of CILL, University of Calcutta.

Contact her at: aratrikaganguly.95@gmail.com

This article is part of the issue ‘Empowering global diasporas in the digital era’, a collaboration between Routed Magazine and iDiaspora. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the International Organization for Migration (IOM) or Routed Magazine.